Irish communities in Rome ended up sheltering some shady individuals during the German occupation of the city…as well as people who might have come just for the craic.

Not only Jews were in danger after the German takeover of Rome in September 1943: much of the adult male population in Rome at the time was liable to be drafted into the new army of Mussolini’s puppet state or press-ganged to toil in armaments factories in the Reich.

The Irish minister to Rome, Michael MacWhite, who was punctilious about Irish neutrality, urged the heads of Irish communities not to shelter state officials who refused to follow the new Fascist government to northern Italy, “as if discovered the consequences would be very serious for all concerned”. According to MacWhite, the Irish Augustinian community at St. Patrick’s in Rome was offered 100,000 lire by one Italian diplomat for permission to lodge there, and similar requests were made to the Irish Franciscans at Saint Isidore’s and to the Pontifical Irish College. All were refused. The Augustinians did briefly take in an Italian officer, the son of the community’s laundress, but embarrassingly had to ask him to leave after consulting the Irish Legation to the Holy See.

On 3 June 1944, just a day before the Germans started evacuating the city, a German deserter turned up at the door of St. Patrick’s and asked to be allowed to stay until he could give himself up to the advancing Americans. But the Augustinian prior, Fr. Thomas Tuomey, produced documents to explain why it was impossible to offer shelter. The soldier, wrote the prior years later, “was very depressed, gave me a German salute and then departed”.

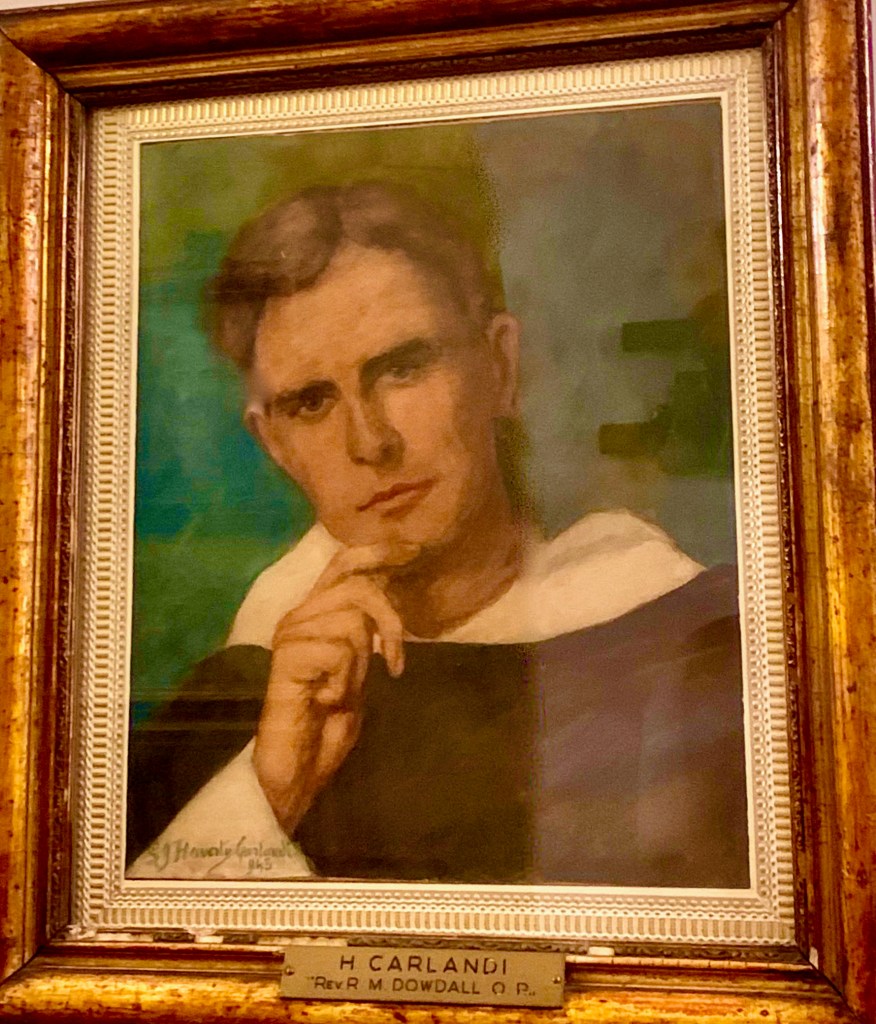

But some Irish communities proved more flexible in their approach to fugitives. At the Basilica San Clemente, run by the Irish Dominicans, the prior, Newry-native Raymund Dowdall, took in five “refugees” in the months after the German takeover. These included a high-ranking foreign ministry official called Count Luigi Vidau as well as “one Jew, one businessman and one Italian barman”, according to Dowdall.

But the most interesting was Fernando Soleti, who had been head of the paramilitary Carabinieri police force. After the Germans seized control of Rome, Soleti was forced to act as a human shield during their daredevil raid to free Benito Mussolini from a remote hotel in the Apennine mountains, where he was being held by the new regime of Marshall Pietro Badoglio. On 12 September 1943, the Germans squeezed Soleti into a glider and deposited him together with a crack unit of parachutists on rough ground in front of the hotel. Whether it was the sight of Soleti being held hostage or not, the Italians offered no resistance.

Along with Mussolini, Soleti was flown to Munich before being sent back to Italy. According to Soleti’s own account, he managed to escape the vigilance of an armed guard and threw himself off the train. Making his way back to Rome by foot, he found refuge at San Clemente. Soleti spent about three months there before leaving for even safer refuge his friends in high places found for him inside the Vatican. San Clemente may have had other guests—although Raymond Dowdall does not mention in his memoir the claim by Tim Pat Coogan that Jewish religious services were conducted there during the war.

As for the Pontifical Irish College, about 20 Italians from the nearby military hospital attempted to seek refuge in the College air-raid shelter on 10 September 1943, during the German takeover of the city, but they were quickly coaxed out. In the following months, according to Rector Denis McDaid, the College received about 10 requests for refuge, all of which he thought “best to refuse”. But the College did take in an Italian officer called Maurizio Pardi, whose mother was Irish. Pardi stayed for two months, along with his second lieutenant.

At Marymount, a girls’ school on the via Nomentana run by the Sacred Heart of Mary nuns, reverend mother Brendan (a Kilkenny native whose family name was Lang) took in Angelo Russo, a painter known to the college before the war and a serving officer in the Italian army. Russo was dressed up in workmen’s clothes and sent around the school garden “digging holes and filling them in, if necessary”. In October 1943, people also found refuge at the Irish Columbans’ deserted premises on Corso Trieste, where the rector was Fr. John Dooley from Shrule in Co. Galway. “Some stay only a few days, some weeks and some for months,” Dooley wrote.

The head of the Irish Legation to the Holy See was TJ Kiernan. According to his wife, the singer Delia Murphy, the Legation “was full of prisoners” by the end of the German occupation, and in complete contravention of the rules of neutrality. Perhaps the most prominent ‘refugee’ there was Moira Forbes, daughter of the Earl of Granard and married to Count Rossi di Montelera (whose family had made its fortune from vermouth). She sought refuge in the Legation in February 1944 along with her friend, the Countess Natalie Vitetti, daughter of an English racehorse owner. After the war, Michael MacWhite had his own view of Forbes’ and Vitetti’s sojourn in the Legation. “I have never heard that anybody was looking for them,” he wrote to Dublin, “but it was very fashionable and patriotic for well-to-do Italians to be in hiding during the German occupation”.