Charles Bewley moved freely between Berlin and Rome during the war in an effort to make himself useful to the Reich

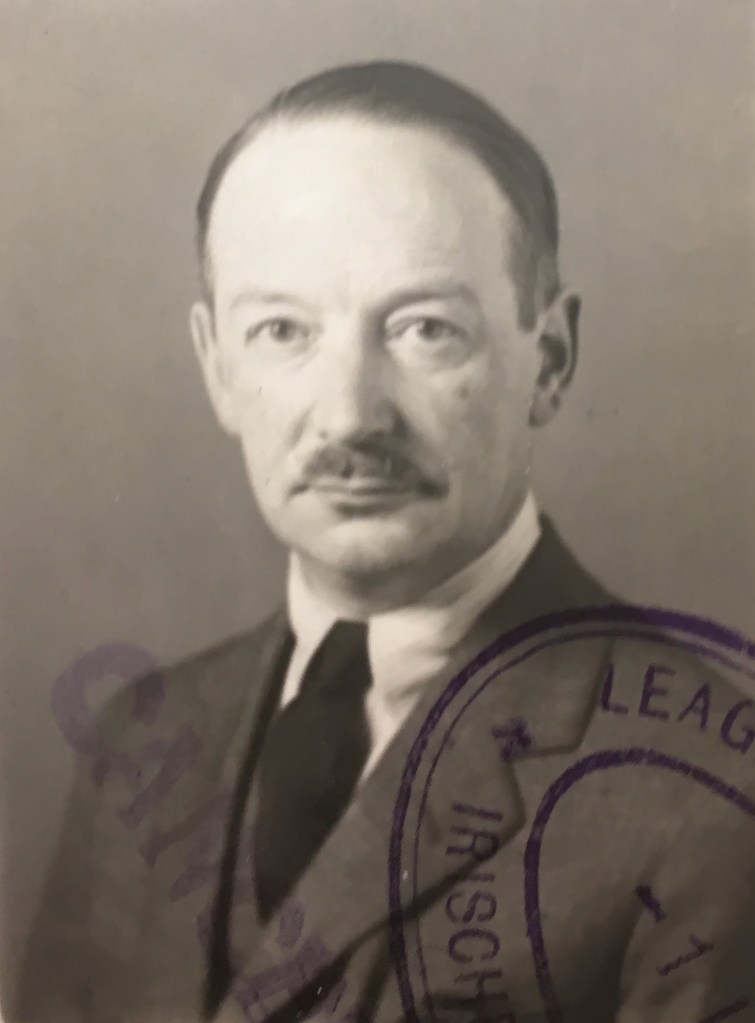

Charles Bewley was born in 1888 the son of a well-off Dublin Quaker family. After law studies in Oxford, he converted to Catholicism and espoused the cause of Irish independence. Bewley was appointed as Ireland’s first envoy to the Holy See in 1929, a position he held until 1932. He was then sent as Ireland’s minister to Germany, travelling all the way from Rome to Berlin in his own car and presenting his credentials to President Paul von Hindenburg on 31 August 1933, just eight months after Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor.

Described as “narrowly anglophobe, pompous and opinionated”, Bewley has become notorious for his report on Kristallnacht, the orchestrated Nazi attacks against Jews and their property in 1938. In August 1939 he was forced to step down as minister in Berlin. Since he refused to accept a position in Dublin, he left the Irish diplomatic corps without a pension after 15 years’ service.

Because he imagined that Ireland would be a backwater once war started, and because he believed, in his own words, that if Germany won, he “might be of some use to Irish interests”, Bewley soon travelled back to Berlin, where he claimed that he turned down a post in the German foreign service. Hanging around the city, Bewley earned money from the sale of his car and from a stream of “well paid” articles he wrote for the German press before setting off for Rome in January 1940.

When he arrived in the Italian capital, Bewley presented credentials showing he had been appointed Rome correspondent for a recently established news agency called Scandia Press, based in Stockholm. The Swedish minister in Rome told his Irish counterpart, Michael MacWhite, that Scandia Press was a front for a German organisation “directed by a gentleman with a club foot” [an obvious reference to Josef Goebbels], while Sir Percy Lorraine, the British ambassador, wrote that Bewley went around Rome claiming to be “on intimate terms with Göring and Himmler”. Another British embassy official wrote to London that he had learned that “the Swiss counter-espionage people look on Mr. Bewley as a spy”. And indeed, Bewley lost no time in reporting back to the foreign ministry in Berlin about his conversations with British and other diplomats posted to still-neutral Italy.

Bewley’s frequent trips from Rome to Germany as well as to Switzerland (where he had a bank account) were closely monitored by Irish diplomats as well as by their British cousins.

In December 1942, Bewley travelled to Berlin along with the Genoa-base Donal Hayes, who had previously tried to smuggle arms from Italy to Ireland during the War of Independence and had been bestowed with the title of ‘Consular and Diplomatic Agent of the Irish Republic’.

TJ Kiernan, Irish minister to the Holy See, wrote in a report to Dublin in June 1943 that during the course of a lunch with Bewley, the latter pulled out a cutting from a Roman newspaper that alleged that Foynes in the Shannon estuary was being used for Allied military purposes. Bewley commented that “this is just the same as giving the use of one of our sea ports to the British and seemed to him a justification for the bombing of Foynes”. Two months later, shortly after the coup d’état that deposed Mussolini, Bewley left for the town of Merano in South Tyrol, a predominantly German-speaking part of Italy that was placed under German administration after the Italian surrender in September.

While safe from Allied bombing and Italian partisans, Merano attracted various rather louche characters like Bewley but was, according to the Irishman, “tedious beyond imagination”. In early July 1944, Bewley managed to secure a place on a sleeping-car for Berlin. Con Cremin, the Irish minister in Berlin told the Department of External Affairs (DEA) in Dublin that Bewley intended to stay in the capital of the Third Reich “working for the Ministry of Propaganda”. It was undoubtedly in connection with such work that Bewley met fellow Irishman, William Joyce, the infamous Lord Haw Haw. Bewley may also have been in Berlin to supervise the publication of a collection of short stories of his in German called ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’, published in Berlin in 1944.

Yet by the end of July, Bewley had returned to Merano, staying there until the Americans arrived at the end of the war. The Americans turned Bewley over to the British, who brought him for interrogation to Florence on suspicion that he had worked for the Sicherheitsdient.

Bewley was then escorted down to Cinecittà, the Italian answer to Hollywood, in the suburbs of Rome. From there, he was escorted to a civil internment camp in Terni, some 100 kms northwest of the Italian capital.

In Terni, Bewley found himself one of 10 special prisoners placed in a block under stricter supervision than the rest of the camp. One of his cellmates was John Amery, 33-year-old son of a British member of parliament who had spent the war disseminating Nazi propaganda and attempting to recruit British prisoners of war for the SS. Amery was taken back to the UK in July 1945 and hung for high treason in Wandsworth prison in December of that year following a trial that lasted eight minutes.

Despite Bewley’s actions, the wheels of Irish officialdom gathered motion to save the former diplomat. In a handwritten note in July 1945, DEA secretary Joseph Walshe mentions a conversation he had about Bewley with Sir John Maffrey, the UK representative in Ireland. “I explained,” wrote Walshe, “that making too much of this man’s part in the German drama would not only be ridiculous but would probably provoke a lot of anti-British comment here. Bewley was an ass—but only an ass. He wasn’t a criminal—least of all a dangerous criminal. It was notorious that he was a complete coward and would not risk his skin for any cause or nation…The best punishment for Bewley would be to show him how unimportant he was, to release him with a kick in the pants, and let him make his way back to Ireland.”

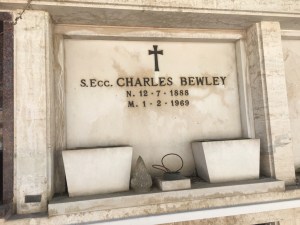

Released in December 1945, Bewley eventually settled down in Rome. Some mystery surrounds how Bewley made a living—although he inherited money from his father and he published a biography of Hermann Göring that sold well. Bewley died in a Rome clinic in early 1969, with his burial in the Flaminio cemetery in large part arranged by his chauffeur, Agostino Cevoli, to whom he left 2 million lire. Despite his troubled relationship with the Irish ministry of foreign affairs, the latter organised a memorial mass for him in St. Andrew’s Church, Westland Row in Dublin.

Leave a comment