Dubliner Darina Laracy contibuted to the anti-fascist activities of one of Italy’s best-known writers during World War Two.

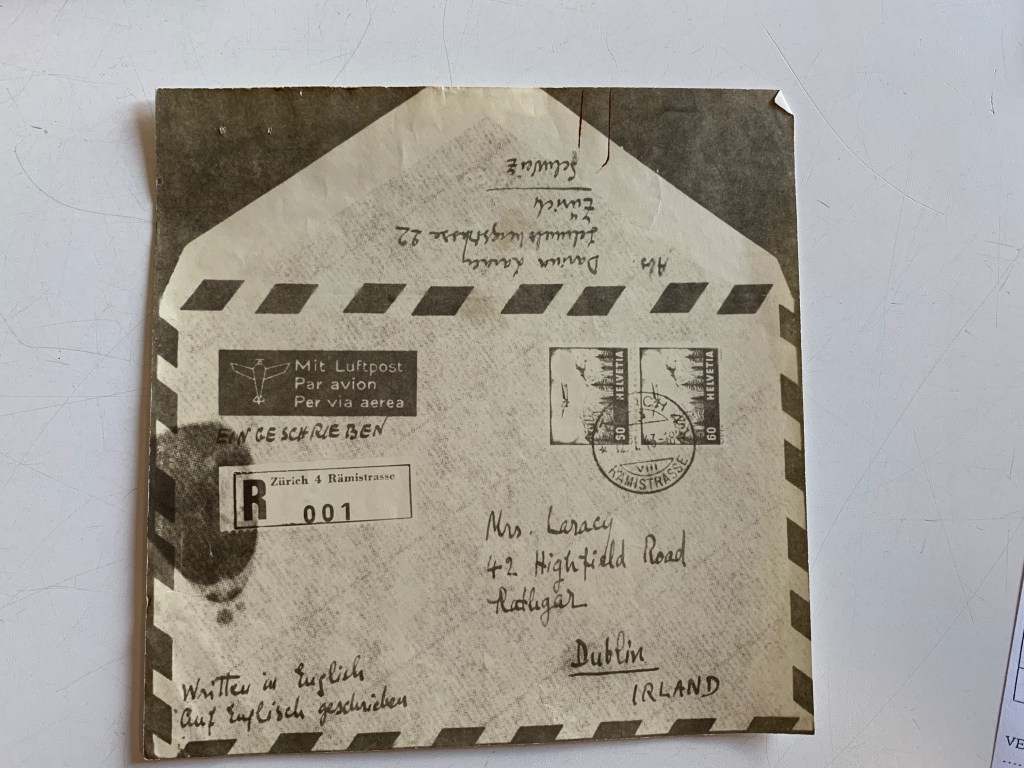

Darina (Elisabeth) Laracy, born in March 1917, came from a comfortable middle-class family that lived at 42, Highfield Road in Rathgar. Laracy graduated with a first-class degree in history and politics from UCD in 1937, followed by an MA, and then won a scholarship to study for a doctorate at the Sorbonne in 1938. Evidently strong willed and resourceful, she managed to make her way down to Rome in spring 1940, before Italy declared war (on 10 June 1940). In the Italian capital, she found work as an “assistant correspondent” working alongside an American journalist called John Whitaker. For 1000 lire per month, she summarised Italian press articles in English, looked after correspondence and attended press conferences at the Ministry of Popular Culture (Minculpop).

The increasingly anti-fascist bent of Whitaker’s articles and his links with the American military attaché led to an expulsion order being issued against him in March 1941. Laracy found alternative work alongside another American journalist, Raymond Allen at the International News Service. But he too was also thrown out of Italy in spring 1941, by which time the Italians’ suspicions were also catching up on the Irish woman.

At one stage, Laracy was approached by Italians working for the Gestapo, who offered her money to spy on the American news organisations she was working for. Laracy maintained that her refusal to cooperate with the secret police explains why an expulsion order was issued against her in spring 1941.

Through an acquaintance, Laracy then managed to obtain a visa for Switzerland, from where she intended to travel on to London via Lisbon. And so Laracy left Italy on 22 June 1941, the same day as Hitler invaded Russia. In Berne, Laracy met Jock McCaffery, ostensibly assistant press attaché at the British embassy but actually in the employ of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the organisation charged with sabotage and encouraging subversive activity in occupied Europe.

Perhaps a personality clash between a tough, ex-seminarian from Glasgow and a south Dublin middle-class sophisticate was inevitable, but Laracy and McCaffery did not meet eye to eye. Laracy later suggested that McCaffery made a pass at her and, when she refused, prevented her from taking up a position at the information ministry in London.

Resigned to sitting out the war in Switzerland, Laracy found work giving private lessons and writing articles for the British daily, the News Chronicle, but largely lived on money her parents managed to send from Dublin. With the short-stay visa that allowed her to stay in Berne close to expiring, she moved to the bigger city of Zurich, ostensibly to undertake research on a book on Italy she had been commissioned to write. She was to stay in that city for most of the next three years, during which time she visited James Joyce’s widow, Nora, on at least one occasion.

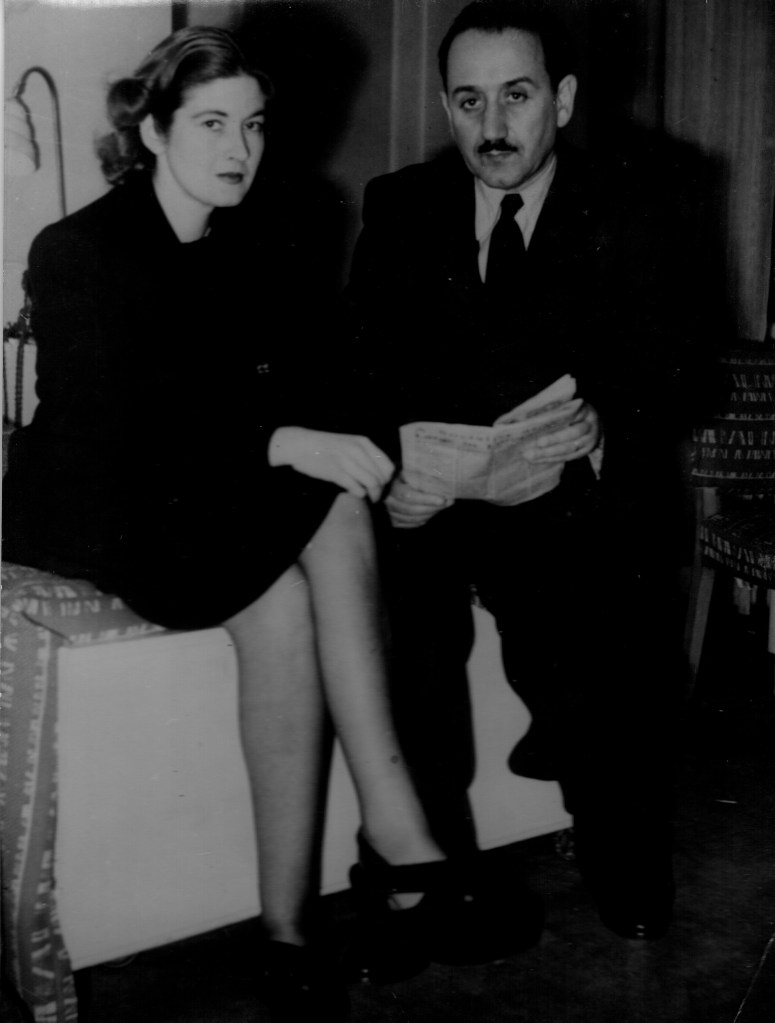

It was in Zurich’s Museumgesellschaft library during the course of her research that she met Ignazio Silone, one of Italy’s best-known writers and one of the founders of the Italian Communist party, who had fled to Switzerland at the end of the 1920s, (by which stage he had moved away from communism and closer to the Socialist Party). Invited to tea by Silone, Laracy told the Italian that she had read some of his books (two of his best known, both translated into English in the 1930s, were Fontamara and Pane e vino) and offered to assist him in his anti-fascist campaigns.

All the time, Laracy, like Silone, was being watched by the Italian secret police, the OVRA, which sent regular reports on her activities back to Rome and intercepted letters she sent to Dublin. Laracy, who was not allowed to reside in any one canton for more than three months at a time, was also closely tracked by Swiss intelligence. In June 1942, she was stopped in the main railway station in Zurich and held in a cell for four days before the police were obliged to release her with want of “concrete evidence of espionage”.

Laracy followed Silone to Davos, finding work at a local school. By this time, Silone had set to work for Allen Dulles, Berne director of the Office of Strategic Studies (OSS), forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency, with Laracy acting as a go-between and translator. In October 1944, the OSS organised for Silone and Laracy to be flown back to Rome, with Silone, who had been exiled since 1927, kissing the ground when he emerged from the airplane. In Rome, the pair were put up temporarily in an apartment in the posh Parioli district, which turned out to have belonged to an Italian army colonel executed by the Germans at the Adreatine caves a few months earlier. In December 1944, Laracy finally married Silone in a civil ceremony.

Laracy, who had no children and had long let both her Catholicism and Irish passport lapse, developed a special fascination for India and Indian mysticism, making several trips to the subcontinent and befriending Indira Gandhi. Towards the end of her life (she died in 2003), she also found herself dealing with her late husband’s political legacy, for archival material turned up suggesting that Silone had been an OVRA informer and had played a role in the arrest of the Italian communist party leadership in 1928–events hat occurred many years before Laracy knew Silone.

Darina Laracy died at her home in via di Villa Ricotti in Rome in July 2003, with her ashes scattered over the Irish Sea shortly thereafter.

Leave a comment